Most fitness plans fail for the boring reasons: motivation fades, life happens, and “I’ll do it tomorrow” becomes an everyday excuse.

This post is about an experiment I’m running to prevent one specific failure mode: the ability to negotiate with myself.

I built FitVow, a small system where I lock real money into a smart contract and, each week, I need to hit my physical activity goals. If I don’t, I pay a fine. The twist: anyone can trigger enforcement and collect part of the fine as a reward, and the rest goes to a charity wallet (Giveth).

I have no control over the enforcement process whatsoever. If I miss my weekly goals, I’m automatically eligible for a fine—no pleading, no explaining, just contract rules.

If you want to verify (not trust) the current state of the experiment, the live dashboard is here: fitvow.pedroaugusto.dev. It reads directly from the blockchain (no backend) and shows the initial stake, week-by-week pass/fail results, and how much has been lost to fines so far.

FitVow is not a product. It’s a personal experiment in motivation: seeing if putting real money at risk succeeds where willpower alone usually fails.

The basic idea

- I stake funds into a smart contract for a fixed time window (e.g., 12 weeks).

- Every week has a set of activity goals (e.g., running, gym, sleep, screen time).

- If I hit the goals, the week is marked as complete.

- If I miss, a penalty can be applied for that week.

- Enforcement is permissionless: anyone can call the enforcement function on the smart contract and get part of the staked funds as a reward for doing so.

- At the end of the fixed time window and I get whatever if left from the stake back.

Think of it as a gym buddy you hand a pile of money to for safekeeping—except he’s allowed to give some of it away every time you skip a workout.

Why permissionless enforcement?

Because anything that depends on my future self being honest and diligent is exactly what I’m trying to avoid.

Permissionless enforcement turns this from “self-tracking with extra steps” into a credible commitment:

- No escape hatch: I can’t just decide a missed week “doesn’t count” by never calling the penalty function.

- No dependency on friends: nobody needs to remember, care, or feel awkward about holding me accountable.

- Aligned incentives: someone else has a reason to press the button when a week fails.

- Free to enforce (besides gas): you don’t need to deposit or send ETH to the contract to enforce a missed week — you only pay the normal network gas fee for the transaction.

That incentive is also why the penalty is split. If I could enforce my own failure and get 100% of the penalty back, the system becomes theater. Splitting it between the enforcer and charity ensures that even if I try to “cheat” by enforcing my own missed week, I still lose real money to charity.

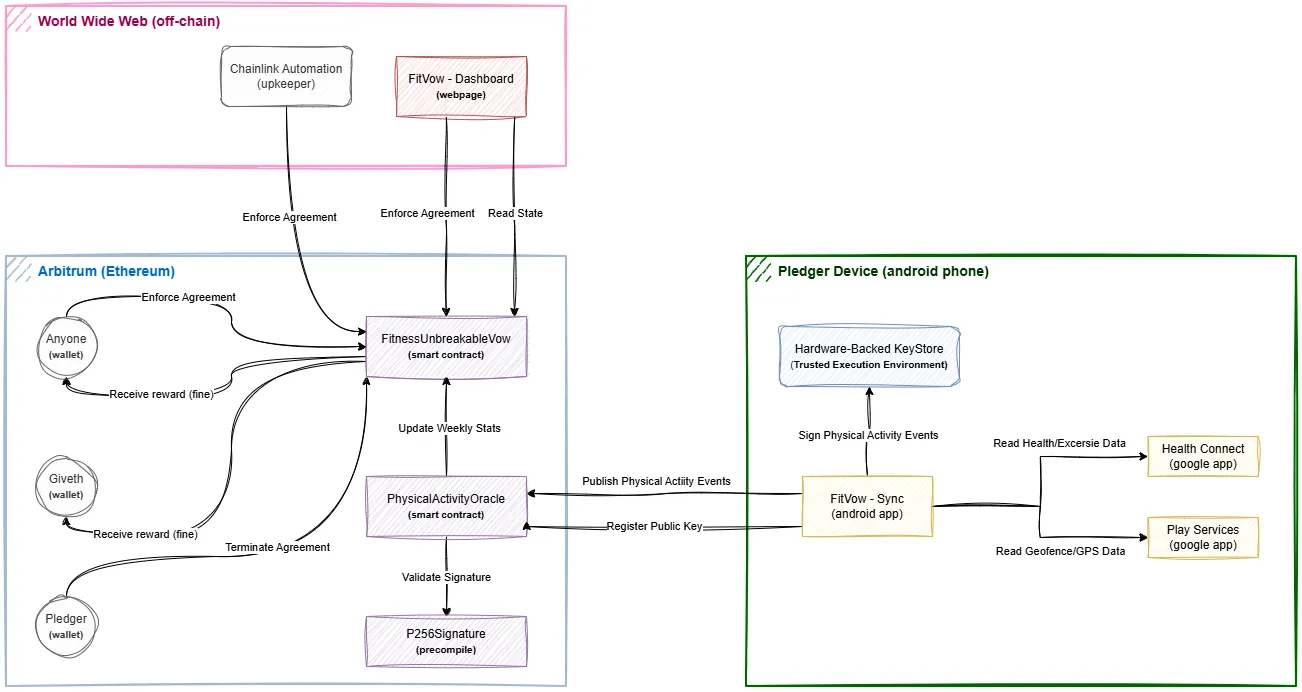

Architecture overview

FitVow is split into three independent components:

-

FitVow-Sync (Android app): A custom Android app I built that integrates with Android Health Connect to read workout sessions recorded by my Samsung Galaxy Watch. It signs weekly activity summaries using a non-exportable, hardware-backed key and publishes them on-chain.

-

Fitness Unbreakable Vow (smart contracts): A set of contracts deployed on Arbitrum (Ethereum L2) that verify the signed activity data, track weekly pass/fail outcomes, and manage the stake by applying fines when a week is missed.

-

FitVow Dashboard (website): A simple frontend that reads from the blockchain and displays the live state of the experiment (stake, weekly results, and fines paid). It also lets anyone connect a wallet with Metamask and enforce a missed week when enforcement is available.

Minimal mental model

- I go on a run for 20 minutes and my watch records the workout.

- The workout is synced into Health Connect.

- FitVow-Sync reads the relevant Health Connect records* for the week, builds a summary, and signs it with a hardware-backed key.

- The signed payload is submitted to the contracts on-chain, which verify the signature and update the week’s status (pass/fail).

- If the week fails, anyone can enforce the penalty and collect a reward, split between the enforcer and the Giveth charity.

* FitVow-Sync filters Health Connect records to only accept data originating from Samsung Health (the Galaxy Watch companion app).

Preventing cheating

If the system were just “check a box saying you went to the gym”, it would be pointless. I could click the box while watching Netflix in bed and call it a day.

So the real challenge is:

How do you make cheating annoying enough that the path of least resistance is simply doing the workout?

FitVow’s approach isn’t perfect, but it tries to raise the cost of cheating by anchoring trust in three places:

-

A wearable-backed data source

Activity data comes from my Galaxy Watch via Samsung Health → Health Connect. A watch produces a bundle of signals (duration, heart-rate patterns, calories/energy estimates, timestamps, etc.) that are much harder to fake convincingly than a manual checkbox. Could someone fabricate it? Probably. But it’s already a much higher-effort attack than “tap to confirm”. -

A hardware-backed signing key (Android Keystore / TEE)

FitVow-Sync doesn’t just upload raw activity records—it uploads a signed weekly summary. The private key used to sign is non-exportable and lives in Android’s Trusted Execution Environment (TEE). This makes “I’ll just run a script on my laptop and submit fake workouts” not work: the contracts only accept updates that prove they came from the enrolled device.To make this verifiable, I also publish the key’s Android Key Attestation on-chain, so anyone can independently inspect the attestation chain and key properties [1] [2].

-

Public, verifiable execution

The rules and state live on-chain, and the code is public. That doesn’t magically prevent cheating, but it does make the experiment auditable. If I try to game the system, I’ll be doing it publicly—with a permanent on-chain paper trail.

The goal isn’t “impossible to cheat.” It’s cheating being more effort than the workout.

Security model (high level)

This system only works if the contract can distinguish “data produced by my enrolled phone + app” from “some script submitting whatever it wants” (aka the sandbox environment). The model is simple: trust the wearable data pipeline, and strongly authenticate the publisher.

Hardware-backed keys (P-256, non-exportable)

On first install, FitVow-Sync app generates a P-256 private key that is non-exportable and stored inside the Android TEE. The corresponding public key is registered on-chain. From that point on, the contracts only accept updates signed by that key [3].

In other words: the contract doesn’t trust “who sent the transaction”; it trusts “who can produce a valid signature”.

Android Key Attestation (verifiable by anyone)

To make that claim auditable, I publish the key’s Android Key Attestation on-chain. This gives third parties a way to verify (via Google’s attestation chain) properties about the enrolled key and environment—e.g. that the key is hardware-backed and tied to an expected app identity/build [4].

This primarily targets the “I’ll just run a modified build or a desktop script” attack.

“Sign-and-forget” builds (amnesiac releases)

A subtle failure mode in mobile security is silent drift over time: new builds, different signing keys, debug toggles, or “temporary” shortcuts that accidentally become permanent.

FitVow treats enrollment of a public key as a one-way door. The enrolled key/app identity isn’t something I casually swap. If I do rotate it, it’s intentionally expensive, so “upgrading into a cheat” has a real cost.

The mechanism: amnesiac APK signing

The FitVow app uses an intentionally non-upgradable signing model.

During release, the APK is signed with a one-time, ephemeral signing key, and then the signing keystore is permanently deleted. After that, it’s cryptographically impossible to produce another APK with the same signature [5].

This is not a mistake — it’s the security guarantee.

Why it matters: on Android, the app’s signing key is the app’s identity. If you ship a future APK signed with a different key, Android treats it as a different app. That forces a reinstall, as opposed to an update, and, crucially, destroys the original app’s hardware-backed (TEE) keys.

FitVow relies on this property:

- the first installed APK generates a TEE key,

- registers the corresponding public key on-chain,

- and becomes the only app instance capable of producing valid activity proofs.

By making the apk signing key unrecoverable, I remove my own ability to:

- ship a modified build while keeping the same app identity,

- and reuse the original TEE keys to submit fake or altered data.

If I want to change behavior, I must pay the full price: reinstall (losing the TEE keys) and use the explicit on-chain key-rotation mechanism.

Auditable releases

To make releases verifiable, official FitVow-Sync APKs are built by GitHub Actions. Anyone can inspect the workflow, review the logs, and download the exact artifacts produced by CI. The version currently running on my phone comes from this build:

Current experiment parameters

This first run is deliberately sized to sting without being life-changing.

- Network: Arbitrum

- Duration: 12 weeks (Jan 19 → Apr 13)

- Total stake: ~$235 (≈ R$1200 / 0.075 ETH)

- Penalty per failed week: ~$19 (≈ R$100 / 0.00625 ETH)

To put those numbers in context (Brazil): my monthly internet bill is R$99 (≈$18), natural gas is R$70 (≈$14), and the monthly national minimum wage is R$1518 (≈$286 💀). So yes — the fines are small, but they’re real enough to matter to me.

...in retrospective, not using stablecoins to keep it simple was not the best idea...

How a week is counted

Each week has three goals. The oracle records pass/fail for each one, and the vow contract uses that outcome to decide whether enforcement is allowed.

The rule for this run is simple:

- ✅ Pass the week: hit 2 out of 3 goals

- ❌ Fail the week: hit 0 or 1 goals → penalty becomes enforceable

The three weekly goals

- Run goal: at least 2 running sessions (as measured by the wearable), each ≥ 2 km, with pace < 8:00 min/km and avg HR > 115.

- Gym goal: a 45-minute gym visit verified via GPS geofence, with avg HR > 95 during the window and max HR > 125.

- Sleep goal: at least 7 hours of sleep (as measured by the wearable), with heart rate in the expected sleeping range.

The “stolen phone” problem (and why recovery is expensive)

If the system only trusts a specific hardware-backed key, then “my phone got stolen” becomes a real operational problem (I’ve had a phone stolen before in São Paulo).

So FitVow has an emergency escape hatch: a one-time key rotation. But it’s intentionally expensive: rotating the enrolled key costs 35% of the current contract balance, and that fee is donated to charity [6].

This is deliberate:

- Key rotation should be for emergencies, not convenience.

- If rotation were cheap, “I’ll just rotate to a modified build” becomes the obvious cheating path.

Think of it as: you can recover access, but you will absolutely feel it.

Automatic enforcement (the “no one showed up” safeguard)

Permissionless enforcement works because other people have an incentive to call the enforcement function when a week fails. But there’s an edge case: what if nobody interacts with the contract?

To prevent “winning by inactivity”, FitVow also has automatic enforcement powered by Chainlink Automation. The key point is that the Upkeep is owned and configured by the Fitness Unbreakable Vow contract itself — once registered, I (the pledger) can’t pause it, modify it, or disable it.

How it works:

- Roughly every 7 days and 4 hours, the Upkeep calls the

enforceAgreement()function. - It’s intentionally scheduled to run after each weekly cycle ends, leaving a buffer so humans have time to enforce first and claim the reward.

- If the Upkeep is the first to enforce a missed week, there’s no “caller” to reward — so 100% of the fine goes to Giveth charity.

In normal circumstances, humans enforce and get rewarded. Automation only exists as a backstop to make sure the vow can’t be bypassed by simply staying inactive. Access the Chainlink upkeep page here.

What this is (and what it isn’t)

This is:

- a concrete experiment in incentives,

- a system design puzzle in creating something I own but can’t tamper with,

- a way to turn vague promises into enforceable rules.

This isn’t:

- a crypto scam,

- a product,

- a guarantee of behavioral change,

- a trustless oracle for all fitness metrics on earth.

It’s a personal project built to answer a narrow question:

Can I design a system where the easiest path is just doing the workout?

Limitations and open problems

A few honest ones:

-

Wearable data isn’t perfect. Sensors drift, vendors change behavior, and APIs evolve. For example, after a Samsung firmware update (Jan 22), my watch stopped reading heart rate reliably on my left wrist and keeps locking itself — real-world hardware is messy [7].

-

Proving “this is the exact APK running on my phone” is hard.

Official FitVow-Sync releases are built in public via GitHub Actions, and the APK on my phone comes from that pipeline. But there isn’t a clean cryptographic way for a random reader to verify my device is running that exact artifact. The best I could do is publish the build logs/artifacts and a screen recording of the installation process on my phone. -

The oracle boundary is still the boundary.

The contracts can only enforce what the android app reports. If the input becomes cheap to forge (or the data source becomes unreliable), the whole system collapses.

There’s also a philosophical limit here: you can’t outsource discipline completely. At best, this is a nudge in the sense of nudge theory—it doesn’t force behavior, it just changes the incentives and reduces the room for “I’ll do it tomorrow” negotiations.

TL;DR

I locked real money into a smart contract and wrote a system that penalizes missed workout weeks. Activity data comes from a wearable via Android, results are published on-chain, and enforcement is permissionless: anyone can trigger penalties and collect a reward, while the rest goes to charity.

If it works, the “easy” choice becomes doing the workout.